Note from Wayward: thanks so much to Felipe Arganaras for once again lending his analytical mind to the blog. Hopefully we can look forward to many more guest appearances!

Last year I was invited to co-cast one of the days of the fourth Coach of Empires tournament. This was an Age of Empires IV 1v1 tournament between new players getting coached in real time by a more experienced player.

As matches went on, we started commenting on how different they were being played compared to previous instances of the tournament, which were played on Age of Empires III. Games were not decided by who had the most solid build order execution but instead by which player was better at reading the match and adapting their composition and approach. This led us to point out some design differences between both games before arriving at a conclusion as obvious as important: adaptability is the defining idea of real time strategy.

In this article I want to expand on my thoughts of that day by looking at the way adaptability takes place in the RTS scene.

What is adaptability?

When people talk about adaptability in terms of games and competitions they refer to the ability of a player or team to change their current course of action in response to changing situations, what is called “piloting a match”.

It’s one of the main attractions of the RTS genre. Players keep with themselves memories of pulling off a seemingly impossible comeback or the thrill of predicting and responding to enemy strategies. Audiences love to see dogged matches between pros, pulling every trick of the book to win or even inventing new ones.

It plays around with the wildcard factor, as well as the overall game design and the players game knowledge. These three elements combine in different ways across many games providing experiences that cater to different kinds of players.

Having many ways to approach the topic, I choose to look at it through the natural evolution of a match, highlighting some design features that provide players with choices and opportunities to interact with the game

Getting into the game

Already at the loading screen, players are fed some initial information to start shaping their strategy: map, starting locations, number of players, factions, player name and ranks.

Map layout will favor some factions or playstyles over others. In a broad term, more open maps encourage mobility and aggression, while more enclosed ones facilitate booming and promote alternate means of mobility. There are maps that feature a particular resource distribution, some provide a security net with resources close to the players bases whereas others concentrate them in certain locations forcing players to contest them sooner or later. Maps play such an important role that games started to offer players the option to veto some of them to cater their favored playstyles or game experiences.

In the same way, the matchups influence army compositions as well as the overall game plan. Certain units may play an important role in certain matchups, for example, the Firebat and the Siege Tank are the only terran units not affected by Zerg’s Dark Swarm and any anti-air unit will be key when going against the Allies in Red Alert 3. The checkmate conditions may also vary, with the most classic example being the boom vs rush faction dynamics, where one will try to stall the other until their advantage wanes while the other will seek to end the match before their opponent has the chance to outproduce him.

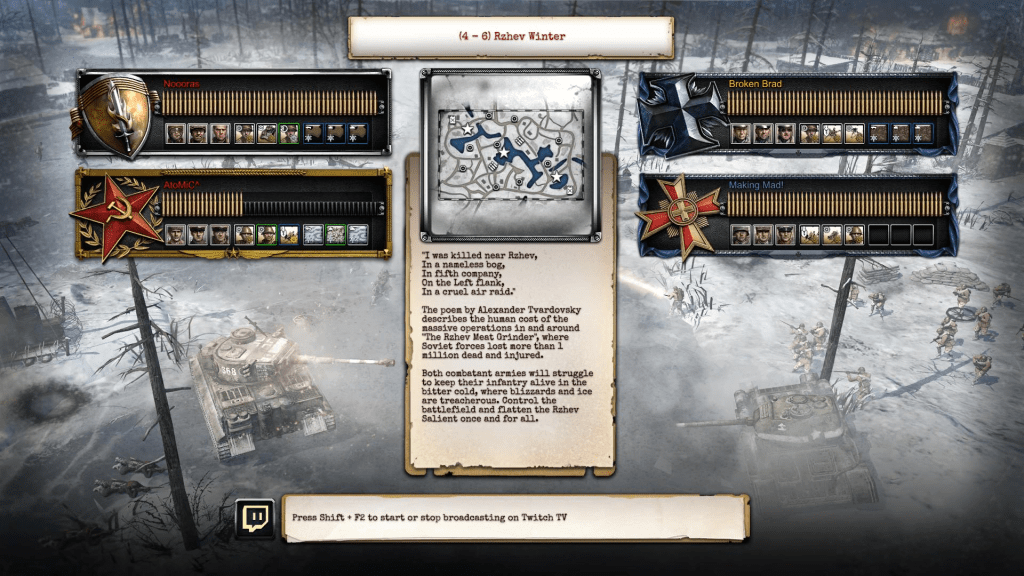

Depending on the number of players, games develop a widely different environment. Team games progressively deviate from 1v1 matches the more players there are, they go from more or less two individual matches taking place at the same time to players having a dedicated role in the team. As such, units may change its impact and strategies viability might vary. A medium tank in Company of Heroes 2 goes from a game changing moment in a 1v1 to a stepping stone into higher tier armament in team games, where it hits a battlefield with a stronger anti tank presence due to higher player count.

Finally, the players name and ranks also influence the players mindset. They will opt for more meta strategies when facing same or higher rank opponents, while being more lenient and experimental against lower ranking players. Getting matched against important, familiar or infamous players will also play a psychological role. Will you play your best against a Pro or just to the bare minimum? How do you feel about having to spend the next 20/40 minutes against some troll who lames your boar or plays the most meta and abusive strategy? Are you going to tryhard with your friends or just want a good time?

Experienced players are going to use all this information to develop an initial gameplan for the match.

The early game

At the beginning of every RTS match there is a blind set up phase where both players are essentially playing on their own or against the environment. This phase is defined by an initial scarcity: players lack means to produce a threatening amount of units to clash with the enemy.

Thus, player behavior at this stage of the game aims to overcome this initial scarcity. It all comes down to securing the means to obtain a resource income that can sustain production, research as well as the progressive expansion of this capacity into higher levels of quality and quantity. This generally means expanding the worker count, securing resources, building new structures to enable new production queues and teching up to unlock new options.

As whoever gets through this phase in the shortest amount of time using the minimal resource expenditure posible has a clear advantage over the opponent, players will experiment with the game mechanics and develop a series of steps to optimize this process. This is what we have come to know as build orders.

We are all familiar with this: send 8 villagers to sheep, send an engineer to capture the Tiberium spikes, use an SCV to build an expansion, get the Mountain King to kill the Kobolds near the base, etc. Savvy players will use the one that works better to the matchup and map, and tweak it on the fly as they see fit.

This isn’t all there is to say about this stage of the game. For quite some time RTS’s devs have been looking for ways to shorten the set up phase or make it more interesting for players. One of the results of this search was the implementation of map objectives which provided a fertile ground for greater experimentation.

By turning map objectives into means to overcome the early game scarcity, the set up phase was made not only shorter and more interactive. It has also allowed players to condition the match even before any side is able to muster the strength to defeat the other.

The Age of Empires series is a great example of the implementation of these trends. Age of Empires II is famous for having an uneventful starting phase, something the devs have tried to address with the Empire Wars format where players start in the feudal age with a premade base and with enough resources to get right into the action, as to make it more appealing for streaming events. Age of Empires IV was built from the ground up to avoid this issue, boosting the starting villagers from 3 to 6, increasing the starting resources and overhauling the role of livestock.

By increasing the number of sheeps available and spreading them through the map, livestock went from a guaranteed food source into an objective for players to compete. The more sheeps a player can secure, the longer he can keep his villagers safe inside its base and the faster his opponent will have to risk his out in the map.

The Command and Conquer series has been doing this since Red Alert 2. Tiberium spikes and oil derricks create points of interest that are fought early on with engineers and rifleman units. These not only provide an early game boost though, as resources in the map start drying up, the unlimited income obtained from these buildings can make a difference in the later stages of the match. There are also other objectives like turrets, radar stations or maybe something as mundane as an abandoned building that can be used to control or reveal portions of the map.

The most finished example of this trend can be found in the Company of Heroes series where the game economy depends entirely on controlling resource points of different values and contact between players happens within the first two minutes of the match. Action is constant, as every point captured results in a benefit for the player and a detriment to their opponent, and the map layout leads and conditions the fight. Victory is even decided by draining the enemy victory points through controlling certain objectives.

The fight rages on

Once we get out of this early stage, we turn our attention to how players capitalize their advantage and how they mitigate their opponent’s. These actions are usually conditioned by how accessible and safe it is to produce units, tech up, expand, defend and the role upgrades play as well as the units themselves.

The player ahead may choose to slow down his aggression and use its advantage to progress down the tech tree to unlock more powerful options as the currently available ones are not enough to defeat the opponent or there are better ways to consolidate the gap with their rival. The most common obstacle that will force a player to tech up are strong bases defenses that can’t be bypassed or inflict too much attrition to the attacking force.

This is because new units or technologies usually introduce new profiles or grant a power spike to already available units. For example, tanks in Company of Heroes can only be damaged by anti tank weapons, negating the advantage of machine guns that previously stalled entire advances; the Adrenal Gland upgrade turns Zerglings one of the most efficient units at surrounding and destroying units and buildings

Sometimes, keeping up the pressure to try finishing off the game with the already available options can force the opponent to delay its own tech to survive and may even strangle him so he can’t capitalize his new tech advantage. This is the case in games where affordable structures allow for the adding of additional production queues to turn the resource excess into more units. This can also be used to neutralize more advanced but limited in number units with large amounts of cheap units.

Games with cheap units and fast training times allow for a faster unit rotation rate (the rate at which units are produced and destroyed) and usually involve the possibility of building new production structures to increase the number of available production queues. On one hand, this means it is easier to mass and upgrade units, but also to switch army compositions. Interestingly enough, the Command and Conquer franchise achieves a similar result using a single production queue per unit type that trains units really fast.

Games with a slower and more expensive process of unit training and unlocking, like Warcraft III or Company of Heroes, rely on other elements, for example, a counterplay system designed around diminishing the combat value of units rather than killing them. The lower unit count and their higher combat value means some units might swing the balance of power of the match, however, appropriate counter play can keep them in check affecting the whole composition. Without that full health Archmage or Sherman Tank, the offensive might lack the punch to make it worth the risk. The higher preservation of units usually comes hand in hand with a more polyvalent role through abilities or upgrades.

This brings us to the topic of units itselves. Having already been covering them across the entire article and in the spirit of keeping this piece as broad and comprehensive as possible, I’ll stick to the unit rosters.

A solid unit roster is another fundamental medium for adaptability, as unit variety sprawls a myriad of opportunities and possible interactions. After all, the units, their stats, bonuses and maluses are the end product of the chain of events that started at the very beginning of the game.

This aspect of the RTS design has seen much polish through the years. Twenty years ago it was fairly common if not the norm to find games with such limited unit availability that the meta was defined by strategies that rushed through the tech tree to unlock the rest of the units or promoted fielding dreaded mono unit builds. Now it has become common practice to have unit rosters that can deal with all the existing unit profiles in some capacity, so even early on there is always some way to respond to any threat (albeit with different grades of efficiency). The Soviet Flacktroopers (Red Alert 3) can counter both air and ground vehicles, but they aren’t as effective at destroying vehicles as the Hammer Tanks or at shooting down planes as the Bullfrogs, but in turn these units can’t fire from the safety of a building and are still vulnerable against anti-vehicle damage.

This design paradigm has proven quite effective, specially in games with asymmetrical faction design, but has also seen use in symmetrical metafaction games, like Rise of Nations.

Another byproduct of the modernization of unit rosters is that no unit becomes obsolete, each one of them can play a role throughout the match, be it through the particular advantages of their profiles or through upgrades keeping their performance on par with units of different tech levels.

The Age of Empires franchise uses a rock-paper-scissors dynamic between its production buildings

Finally I would like to mention the role played by force multiplier mechanics such as height advantage, garrisons or cover systems. These kinds of mechanics intertwine with the engagement dynamics, reinforcing map design by adding another layer of complexity and contributing to shape the match pace and possible strategies. A dominant building or a cliff can be used to lock down sections of the map, hills may turn into defensive linchpins. However, I find their most interesting application happens during random engagements in which players will have to make split second decisions on the unit positioning for maximum advantage, turning battles into a dance between the opposing forces.

Closing thoughts

These are some of the most widespread game mechanics and design choices devs have been using to create an engaging experience for players across many games through the years. Many of these topics can be covered in much more depth and there are still many others I didn’t manage to cover in this piece, but this article is already quite long as it is.

This wasn’t an easy piece to write, but the journey has been an amazing experience that allowed for many enthralling exchanges at Discord. Charting the evolution of some of the design practices has been a thrilling experience and figuring out the effect every one of them have in creating a particular experience was a nice exercise in introspection.

I think this article can help us to bring to the forefront the role each piece of the game has in creating a dialogue with the player, as well as some initial elements to comprehend why some modern RTS’s have fallen short trying to emulate the most successful formulas of the genre.

Age of empires IV is one of the worst RTS ever, they totally ruined the experience with cartoon art style, very simple mechanics to attract kids, kids that don’t play RTS and play fornite instead.

LikeLike